HOW CAN INNOVATIVE THINKING SURVIVE RESEARCH?

You've got a great idea for a new campaign or offering that's based on a thoughtful and compelling customer insight. And then you hear three words that make you die a little on the inside:

"Let's test this."

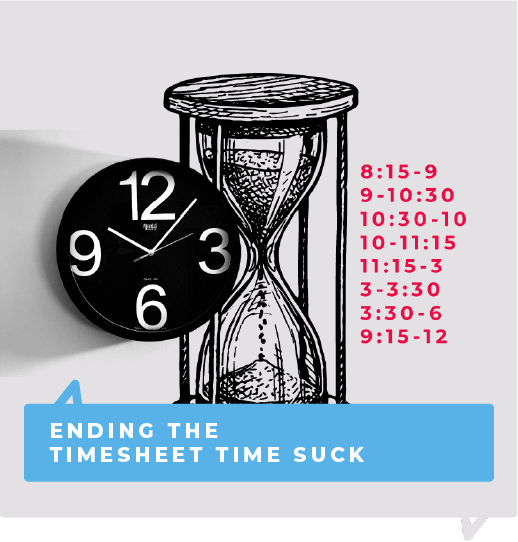

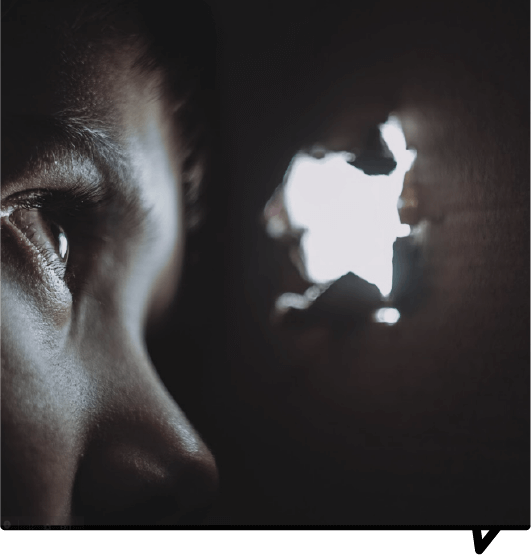

If you've felt this way, it's because you're an experienced enough designer or marketer to know the old saying is true, "research is where great ideas go to die." I've spent countless hours behind the glass watching random samples of customers as they take an hour out of their day to critique innovative thinking with little or no context. All too often, concepts we're all super-excited about are slowly diluted down to the point where they lose what made them special, or thrown out entirely in favor of something that everyone can easily agree on.

It's understandable why gaining a large consensus looks like success, but what are you gaining consensus around? If the metric of success is what's most likeable and easily digested by a large group of people, well, that's not really aligned to the idea of innovation.

If you look into the stories behind innovation we take for granted, from electric lights to disposable diapers, to cellphones, there is always resistance and derision to new thinking. I'm old enough to admit that, when I started my first professional job, they were in the process of switching from a paper to an online system billing system. During the IT training session on the tool, you would've thought the company was asking longtime employees to sacrifice their firstborn when asked to save some time and resources by using their desktops to enter hours.

People in general have a hard time conceptualizing really innovative "outside-of-the-box" ideas and solutions, let alone understand how they could implement them into their lives. Why? Because we're asking people to go against instincts and behaviors they've built over time, slowly, which are reinforced with our own experiences and beliefs. People go with what they know because it's ingrained and easy to do. Real innovation is disruptive and challenges the status quo. It can ruffle feathers and make people confused or even uncomfortable.

Does this mean research around innovation is useless? Absolutely not. Instead of using research as a safety net at the end of the process, we can use it as a whetstone to sharpen our thinking if we re-consider how we're asking questions, who we're talking to, and what we're asking.

HOW WE ASK: IN AN ARTIFICIAL ENVIRONMENT

The normal set-up for qualitative research is in an unfamiliar setting surrounded by unfamiliar people. When people walk into an interview or focus group, they register the thought that they're being watched and judged by strangers both behind the mirror and sitting next to them. Instead of being honest, people tend to put their best self forward when they're in a forced group dynamic. Entertaining at times, but not as helpful as it could be.

WHO WE ARE QUESTIONING: RESISTERS

Mass acceptance and adoption is the grand prize for innovation, and it's tempting to take our new idea to those who represent the mass market (and ultimately present the largest opportunity). The general consumer population is fantastic to engage when you're uncovering a problem to solve, as just about everyone is great at letting you know what's wrong. However, are they the right group to present a unique solution to? As the majority of people are resistant to change, does it make sense to get their opinion on something that forces a fundamental shift in their thinking during a 45-minute discussion?

WHAT ARE WE ASKING: LIKEABILITY VS COMPELLING

"Is this something you think is interesting?"

"Based on this, would you consider buying?"

"Would you say this fits you and your lifestyle?"

All of these questions basically boil down to the same thing - do you like this? Being likeable is fine, but it's rarely the hallmark of transformative ideas. If likeability is the deciding factor, know that the idea that's easiest to accept within the artificial environment is what will win. While your new idea or product might do well in the marketplace for a bit, "likeable" is rarely memorable or exciting. Imagine a friend trying to set you up on a blind date and you ask them to describe this potential love interest. If they led with, "well, they're really likeable," it probably wouldn't get you all that fired up to put on your good pants and go out to dinner.

We should re-think our approach to validation and design and apply research that helps to make the thinking more meaningful instead of diluted. You've worked long and hard on that new idea; the approach to how you pressure-test its merits can and should be just as innovative.